Arpita Shah

Can you introduce Nalini and tell us what it was like to embark on this journey. Including what it was like to replace your studio practice with heading to locations that gave you insight to the stories of the woman in your family. Where did their history take you that you had not yet been? What timeline does Nalini cover?

Nalini is an ongoing project that focuses on my mother, my grandmother and myself. It explores the intimacy, distance and longing between the generations of women in my family that have grown up and lived across various continents and cultures.

‘Nalini’ is my grandmother’s name and the project was inspired by her. She was born in India but spent her childhood in East Africa before moving back to India. Although I visit her in India every couple of years, I realised how little I really knew about what she was like as a young woman, her memories, experiences and relationships. Each time I see her, she get’s a little frailer and more forgetful - so I started this project to learn more about her and my female ancestors, because I wanted to feel closer to them and I didn’t want their stories to get lost.

The series comprises of personal objects, family archives and photographs of landscapes, still lifes and female family members. This was a very different approach for me as my previous work is much more studio based, however I felt it was really important for Nalini to reflect on and evoke certain memories, emotions and experiences - so capturing particular textures, tones and light was really essential. And, on a more personal level, it was also really important for me to physically and symbolically return to the various landscapes linked to my family as a way for me to connect to their memories.

So alongside developing the project across UK and India, I also travelled to Kenya for the first time with my mother, to visit where my grandmother and great grandmother had lived during the 1930’s. This is where I’d say the narrative of the project begins.

What symbolic meaning or role do the flowers play within the images of Nalini? Can you tell us why certain objects became important to include and how they relayed your memory or understanding of your own history?

Nalini is the Sanskrit word for lotus flower, which in Hindu mythology symbolises fertility, the womb and rebirth. My work often references lotus flowers and particular flora from Indian mythology to evoke experiences of displacement and the female life cycle. In Hinduism, flowers are very sacred and often used as offerings to ancestors. So I wanted to touch on all these themes in the series, which is why flowers reoccur in my images in various forms.

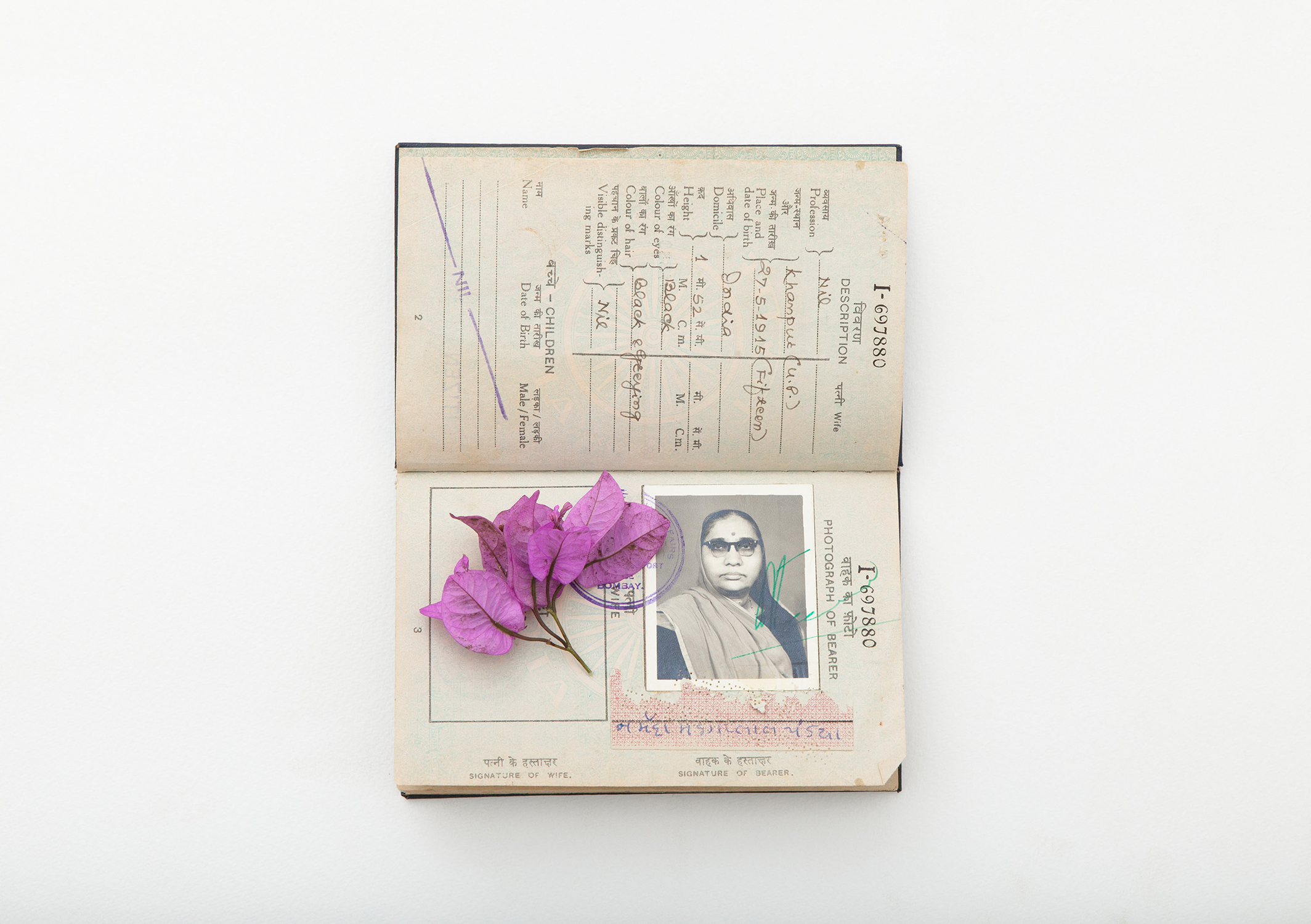

Alongside photographs of flowers, landscapes and maternal bodies, Nalini also displays particular objects. Some of the objects are photographed in staged shrine-like still life assemblages; like the photograph of my great-grandmothers Indian passport decorated with freshly plucked bougainvillea.

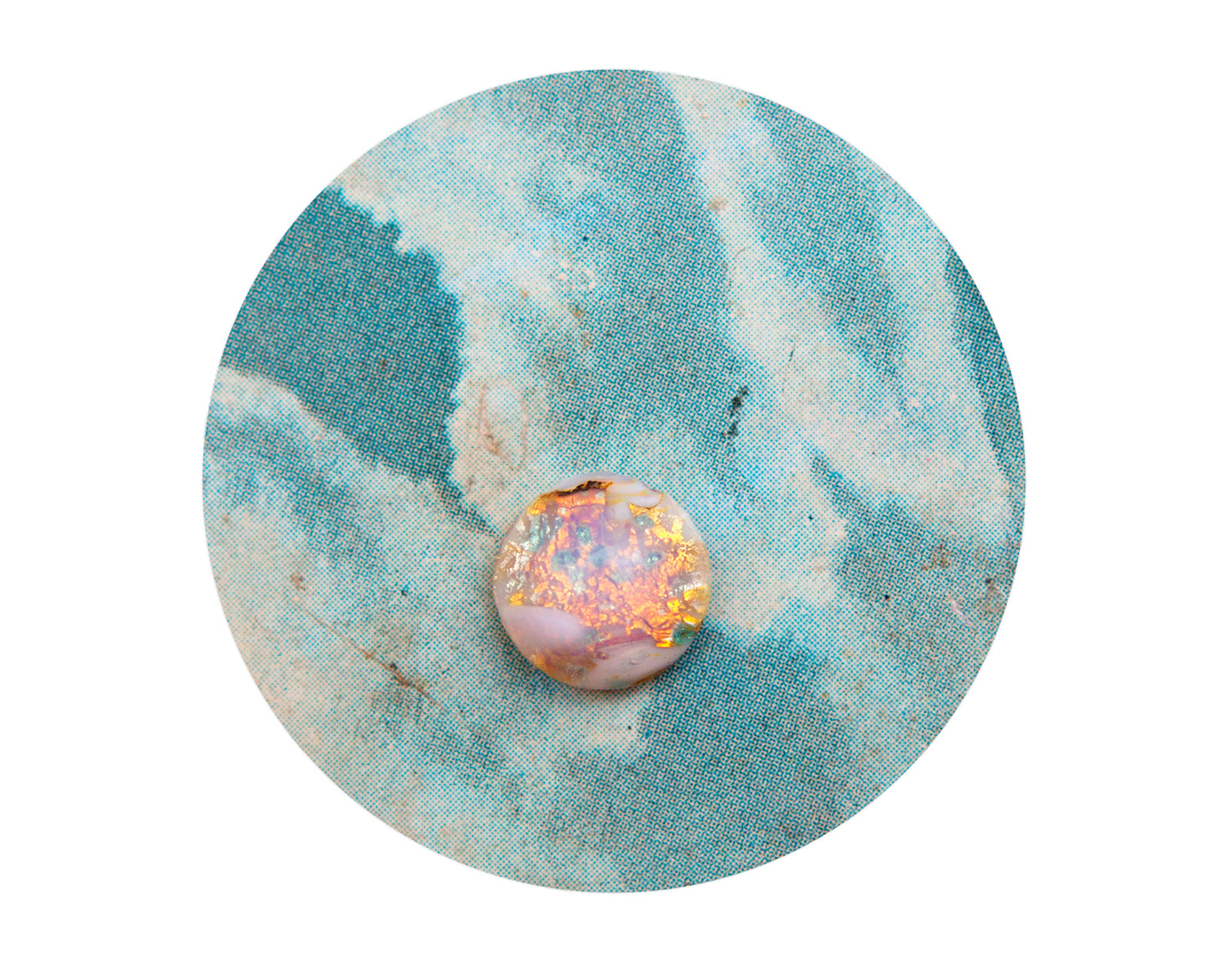

Other objects are presented in physical form such as an old Taj Mahal sweets tin, opal stones from Kenya and crumbling studio family portraits from the 1920’s to 1960’s from India and Kenya. These objects have travelled across continents through time and through generations, as artifacts of my family’s journey. It was important to include them because they bare little scratches, scars and creases. Like the body they have aged with time, full of stories and experiences.

One significant object is my great grandmothers silk sari from Nairobi, which was passed down to my grandmother, to my mother and now to me. Fabrics, and specifically sarees are something that I often photograph in my work as a way to explore my cultural identity. As an Indian woman, there is something incredibly powerful in being able to perform the same rituals of wrapping a sari around your body in the same way your female ancestors did. Knowing my great grandmothers sari was once wrapped against her body, then my grandmothers and mothers, and now by me, is really powerful.

In the quest to preserve your own family history what did you discover about your Grandmother or Mother than surprised you? What information did you learn about them that taught you more about yourself?

When I started initially researching for Nalini I started interviewing my grandmother, mother and female relatives – sometimes individually and sometimes collectively. It was really interesting how in the group conversations, one memory often triggered another family members memory – sometimes this led to the unlocking of certain lost memories. So it was really amazing and very emotional at times to hear stories that I’d never heard before. These conversations led to many new discoveries about my family and evoked emotions that I’m not sure would have emerged if I hadn’t started the project. Essentially this brought me closer to my grandmother and in a sense to all my female ancestors; to be able to remember them collectively and laugh and cry was really powerful.

After these interviews, I started photographing my mother and grandmother and it was really interesting discovering certain physical similarities that the three of us share. Forms, postures and curves I’d never spotted before until I started observing them through the negatives of film.

I think the most significant experience was my relationship with grandmother, this project brought us closer. I can speak in Gujurati, but find it really difficult to express myself, so in the past my mother or aunt would always be translating between us. But when I started working on Nalini, Grandmother and I would spend hours together, sometimes trying to understand each other and other times in silence. For me that silence and the process of slowly photographing her was so much more intimate than language.

Why do you feel its important to preserve family history and what will Nalini allow you to pass on to the next generation of your family?

I think many of us long to preserve or discover more about our family history, before it gets lost. For me, having moved around so much I’ve never grown up with my extended family in India, so have always longed for them. I can’t really articulate in words the emotions of discovering for the first time a crumbled photograph of my great-grandmother standing elegantly in a photography studio in Nairobi with a stamp dated 1939. But it was an incredibly powerful moment, and if I hadn’t started this project I’m sure this image would have decayed and disappeared in the attic I had found it in.

We all have elders in our family who are full of stories and once they are not around anymore where do these oral histories go? It’s been amazing adventure to be able to rummage through attics and collect family photographs and oral recordings of family members, because these are things I can pass on to the next generation. So one day, when they want to know more about our ancestors and Indian heritage they can listen to the interviews and look at the digital archive I’ve created - and I can only hope they’ll feel how I did when I discovered that studio portrait of my great grandmother.

Nalini has been featured in exhibition form, as you will be working with Light Work AIR in Syracuse this September to begin translating Nalini to the format of a book, how will the intimacy of Nalini translate in print versus exhibition? Since this work is personal what factors did you consider when choosing the exhibition layout (image size, text) to display your story? What factor or consideration do you anticipate will change when creating the book of Nalini?

When I started making images for Nalini, as part of my process, I was subconsciously laying images out and responding to them in sequences and diptychs as if for a photobook or a diary. So, when it came to planning to exhibit Nalini, the editing process became quite tricky at times because I’d never displayed such intimate photographs and personal stories before. I sometimes felt quite over protective over some of the images and felt quite vulnerable. But in another way, I saw it as an amazing opportunity for me to create a physical space where I could piece together my family’s fragmented histories and identities. I really played with scale and format, so some pieces were shown almost life like and others were displayed much smaller and more intimate.

Because there is not one single linear narrative in Nalini, some stories and photographs were included in the exhibition and some were left out – perhaps to be presented in the book. Nalini is ongoing and like all family stories, the narrative keeps evolving and shifting - so it will always take different forms each time it’s shown. I anticipate the book will be easier in one sense but also harder. With a book there is a more defined physical beginning and ending, as with an exhibition you can be much freer with the narrative and sequence of where the exhibition starts and ends.

But in terms of the book format, my images have this textural element which invite viewers to touch, and I think presenting them on pages would really add to the notion of longing, memory and loss that I’m exploring in the work. This will be my first photobook so I’m extremely excited about going to Light Work in September and developing Nalini into it’s first publication.

To keep up to date on Arpita’s upcoming work follow along here:

Instagram https://www.instagram.com/arpitashah_/

Website http://www.arpitashah.com/